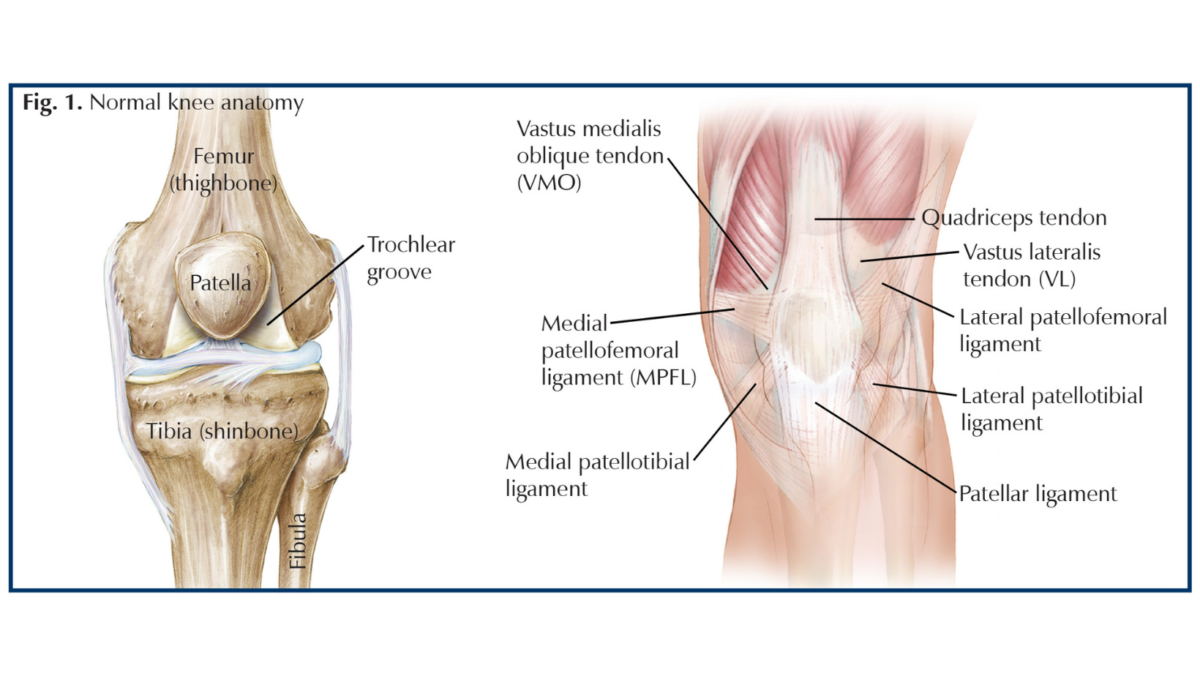

During a traumatic event, such as a fall, auto accident, or sports injury, the patella (kneecap) can completely or partially dislocate. A patellar dislocation occurs when the patella “jumps” out of the trochlear groove (a groove that holds the patella in line) and usually moves toward the outside of the knee. With patellar dislocations, often the most recognized damage is to the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL). A MPFL tear allows the patella to move out of place; and then, when it returns to its normal position, the patella damages the trochlea, causing bone bruising or fractures. Three bones form the knee joint—the tibia (shinbone), the femur (thighbone), and the patella, and these bones are held in place by a group of ligaments (tissues connecting bone to bone) and tendon (connects muscle to bone). These include the patellar ligament, medial and lateral patellotibial ligaments, medial patellofemoral ligament, and quadriceps tendon. As you move your leg, the patella glides up and down on top of the femur inside the trochlea (Fig.1).

Symptoms

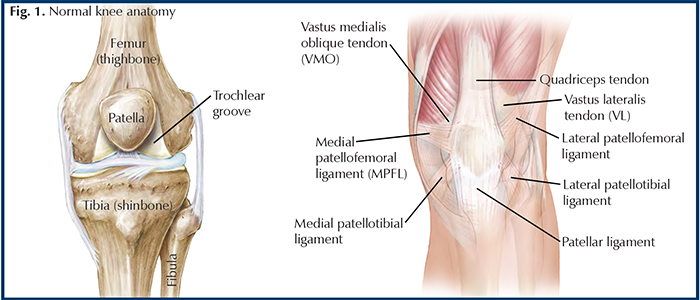

Patellar dislocations occur most commonly in young athletes and can be a result of a direct blow to the knee or patella. After a kneecap dislocation, a patient often experiences pain, swelling, and hemarthrosis (a collection of blood) in the joint. The kneecap usually is displaced toward the outside, but the appearance of the knee may lead the untrained eye to think the patella moved toward the inside because the shape of the large medial femoral condyle, the bony projection at the end of the femur (Fig.2). It may be painful to walk or to bear weight and the range of motion of the knee may be limited. The patella may need to be reduced, or put back in place, or it may spontaneously reduce (return on its own). The doctor can perform the

reduction by gently straightening the knee and placing a side-directed force to the patella. After reduction, an immobilizer or hinged knee brace is worn to keep the knee in full extension (straight) to protect it from dislocating again while it heals. This injury can have long-term consequences, such as instability of the patella, pain, recurrent dislocation, and patellofemoral osteoarthritis.

Diagnosing the injury

An orthopedist should examine your knee after a patellar dislocation. During the doctor’s visit, the physician will take a medical history and perform a physical exam, which helps evaluate the nature of your injury. Your physician will order x-rays and may elect to order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, a scan that shows the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments). Not all first-time patellar dislocations require an MRI, but based on the severity of your injury and the results of your physical exam the test can help determine the extent of other damaged structures within your knee. During the visit, the orthopedist will likely ask questions to help determine the course of treatment. For example, is this the first time you have injured your knee or have you had other problems with your knee before. The information can help determine if the injury is due to trauma, if it is the result of malalignment of the patella, or if you have a history of patellar instability.

Nonsurgical treatment

Your orthopedist will decide on a course of treatment based on information ascertained about your knee and the history of your injury. Initially, your physician may elect to have you wear a brace that allows minimal weight-bearing, control pain with medications, and have you transition to a physical therapy program. During physical therapy, range of motion will be the focus for the first 4 weeks. Then, strengthening exercises start around 4 to 6 weeks and sports-specific training between 6 and 10 weeks. Often, you can return to sport at 10 to 12 weeks as long as there are no other dislocations.

Surgical treatment

After a course of therapy, if your patella continues to dislocate or feels unstable your surgeon may offer surgical intervention. Surgery would include knee arthroscopy, to look at the inside of the knee for damage, and an open procedure to stabilize the patella. This can be done with a procedure called proximal extensor mechanism realignment. This procedure takes tissue available in the knee and tightens the stretched-out structures. It also loosens tighter structures to balance the forces of the patella, and the trochlea groove it slides in. After the arthroscopic portion of the procedure, a 3 to 4 cm vertical incision is made over the upper portion of the patella to gain access to the vastus medialis oblique (VMO) and vastus lateralis (VL) tendons. While the knee is bent at 30 degrees the VMO attachment is removed from the upper inside pole of the patella. It is then advanced (pulled) over the superior medial body of the patella, essentially tightening it, and reestablishing stability as this is the loose side. With the knee still bent, the VL is also released in a similar fashion; however, it is reattached to the center of the patellar ligament; thereby loosening the more contracted side. This surgery is usually an outpatient procedure or a short 23-hour hospital stay. Risks include infections, blood clots in legs, problems with anesthesia, stiffness of the knee, and damage to nerves, arteries or veins.

Returning to your sport

After surgery, rehabilitation is similar to early conservative treatments, such as physical therapy that first concentrates on range of motion, then strength training, followed by sports-specific training. Your physician will not recommend returning to your sport until you have reached the strength and agility levels you had before injury. You should not be surprised if it takes you a little more than 3 to 6 months to return to your pre-injury level.

Author: George B. Sutherland, MD | Savannah, Georgia

Vol. 30, Number 2, Spring 2018

Last edited on October 18, 2021